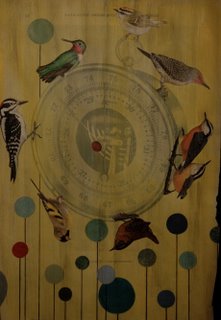

on zitting cisticolas & spotted pardalotes

Field guides rank high on my list of life’s excellent things. You can open them anytime & discover a creature new to you; transport yourself to another world by, say, reading about flora typical of wetlands in the Indus valley in Pakistan; or simply confirm the identity of a visitor to your back-yard feeder. And if you’re fond of words, well, there’s an abundant supply of specialized vocabulary & downright good names in books about insects, mushrooms, or tropical fish. All this & plenty of illustrations, too—what’s not to love?

Peterson’s guides have long been the standard, & deservedly so; you can’t go wrong spending part of your paycheck on any volume in that series. The huge popularity of birding means more bookstore shelf space devoted to the subject than ever before, & in the interest of keeping today’s post a manageable size, I’ll mention several notable entrants in the wing & beak category.

National Geographic’s “Field Guide to the Birds of North America” has been the one I reach for most often, & the fifth edition, published earlier this year, contains 967 species. The familiar northern cardinal & American robin are here, of course, but so too is the tawny-shouldered blackbird, an accidental sighted in Key West back in 1936. In other words, if you’ve got out your binoculars in the United States, whatever you encounter is going to be in this book. The plates are lovely—more than once I’ve turned to the index for the name of the artist (Cynthia J. House paints ducks stunningly; H. Douglas Pratt & Diane Pierce are great with songbirds). Indexes of bird families & species on the cover flaps allow you to quickly locate the sections on woodpeckers, hawks, or warblers.

Princeton University Press rocks. I own “Birds of Australia” & “Birds of Kenya and Northern Tanzania,” but I’d gladly make room for a dozen more titles. While the illustrations may not be as consistently fine as National Geographic’s, nearly a third of “Birds of Australia” is given over to “The Handbook,” highly readable notes on behavior, nests, courtship, breeding, & migration. There you’ll learn that lorikeets have specialized brush-tipped tongues for collecting nectar or see the diving sequence of the azure kingfisher. Australia’s geographic location means it has loads of endemic species (12 types of fairywrens & 41 kinds of honeyeaters alone), which are indicated by an E in the field information opposite the plates. As with the Australian guide, when you flip through “Birds of Kenya” you’ll be treated to a host of avian wonders. Wattle-eyes & batises, leaf-loves & bristlebills, widowbirds & whydahs—no wonder birds find their way into poems so often. I particularly delight in the pages depicting what must be a gerund-crazed species, the cisticola. Besides the singing & the whistling varieties, there are also the trilling, rattling, croaking, winding, siffling, wing-snapping, & zitting cisticolas.

Another Princeton offering is “Finches and Sparrows” (1999), which is concentrated beauty, since it focusses on two of the most colorful & attractive bird families. Every plate is dazzling, &, as is expected from this press, the notes are excellent. Spend an hour of two in the company of red-eared firetails, dusky twinspots, & magpie mannikins—you’ll be glad you did.

Although I tend to prefer guides that feature artists’ renderings, the quality of photography has risen impressively in recent years, & “The Shorebird Guide” (Turtleback, 2006) is astonishing in this regard. Its extensive detailing of the seasonal changes within a species—juvenile, breeding, or molting birds can appear quite different from each other—is essential information, but the full-page portraits that occur throughout the volume are gorgeous. I marvel that we are on the same planet as these birds.